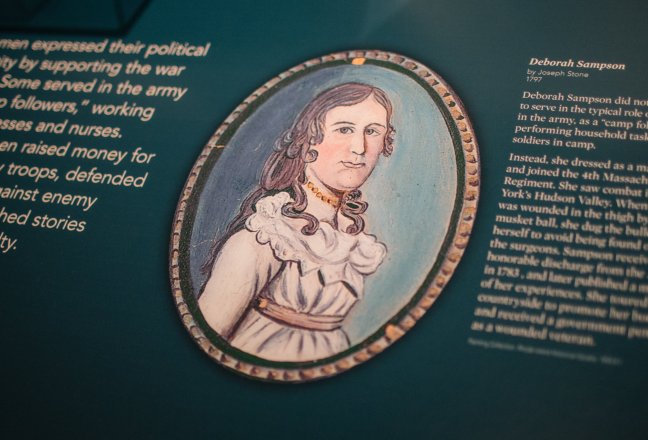

American Revolution | Deborah Sampson of the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment

The American Revolution was a time that people really stood up for their beliefs and took a stand for the things they felt to be right whether it was for the cause of patriotism or King George III. The two sides had people rushing to do their part.

Loyalty was seen throughout both genders and an excellent example of this would be a bold woman named Deborah Sampson. She was a female patriot that refused to allow gender roles to define her actions. Ms. Sampson was a young woman that had the audacity to want to fight for the colonies right to govern themselves. England’s heavy taxation through the sugar acts, stamp acts, and other goods played a significant part in the boiling point leading to the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1776.

Deborah Sampson defied all gender expectations to take part in the efforts. The woman was a true renegade. The thought of a female going anywhere near the battlefield in any fighting capacity had been unheard of. There are people that think women should not be a part of infantry to this day. The importance of these actions in the 18th century speaks to female strength, wisdom, influence, and rights.She took power into her own hands and did as she wanted without holding back.

The risk and consequences were enormous.

The family of Deborah Sampson are direct descendants of settlers who arrived over on the Mayflower when the British Colonies were first being built in the Americas. She was born in Plymouth, Massachusetts on December 17th, 1760.

Deborah was the first of seven children that Deborah Bradford birthed. The family suffered many difficulties because of financial instability. The Sampson children grew up poor. Deborah’s father Jonathan Sampson Jr. abandoned the family after losing out on his father’s inheritance to his brother-in-law.

In the History of Massachusetts archives cited from biographer Herman Mann, suggested that the family believed Jonathan Sampson left to go off to sea in search of getting a fortune to support his large family. Reports showed that he had perished during his travels. Herman Mann interviewed Deborah Sampson himself and wrote:

“He [Johnathan Sampson, Jr.] met with a sad disappointment in his father’s estate, occasioned by the ill designs, connivings and infinuations of a brother-in-law. Thus, he was disinherited of a large portion that belonged to him by hereditary right. This circumstance, alone, made such impressions on his mind, that, instead of being fired with a just spirit of resentment and emulation, to supply, by good application and economy, that of which he had been unjustly deprived, he was led into opposite pursuits, which she [Deborah Sampson] laments, as being his greatest misfortune. Such was her father’s local situation after his marriage with her mother. She informs, that she had but very little knowledge of her father during her juvenile years. Despairing of accumulating an interest by his domestic employments, his bent of mind led him to follow the sea-faring business, which, as her mother informed her, he commenced before her birth. However great his prospects were, that fortune would prove more propitious to his prosperity and happiness upon the ocean, than it had done on the land, he was effectually disappointed: – For after he had continued this fruitless employment some years, he took a voyage to some parts of Europe, from whence he was not heard of some years. At length, her mother was informed, he had perished in a ship-wreck.”

It came to light in later reports that this actually was not the case. Jonathan Sampson had a relationship with a woman named Martha leading to a common law marriage and two children. Records show that he lived the rest of his life out in Lincoln County Maine until his death in 1811. He had never gotten himself out of poverty.

The Sampson children were originally raised by their mother but at a very early age had been scattered to live among relatives. Deborah’s mother was unable to support so many children and suffered from very poor health that affected her ability to take care of the large family. Deborah Sampson’s childhood was very hard and tough. At the age of ten years old, the young girl became an indentured servant to the household of Jeremiah Thomas who had a large family of ten.

The Biographies of Distinguished Women explains that Deborah “for ten years helped with the housework and worked in the field. Hard labor developed her physical strength. In winter, when there wasn’t as much farm work to be done, she was able to attend school. She learned enough so that after her servitude ended in 1779, she was hired as a teacher in a Middleborough public school.” It is without a doubt that Deborah was strong and had a thirst for knowledge. She wanted to live with purpose and had been raised to earn her way through life doing her absolute one-hundred percent best.

The Thomas family had a farm in Middleborough, Massachusetts and tons of young male children. Deborah would assist the boys with their studies in the evening when she was unable to attend school because of work and chores in the households. Indentured servitude was an extremely hard life to live. Luckily, there are no reports indicating that the young girl had been mistreated by the Thomas family. Yes, she had to work hard for them but they also housed, fed, and educated her. In the book titled History Of The Town Of Middleboro, Massachusetts by Thomas Weston, the author illuminates the massive effect Jeremiah Thomas had on shaping Deborah’s character and political interest. Thomas Weston in his biography of the town and its occupants wrote:

“Mr. Thomas, as an earnest patriot, did much towards shaping the political opinions of the young woman in his charge, who early developed talent and a strong desire for knowledge. Her perceptions were quick and her imagination lively; she soon became absorbed in the stirring questions of the day.”

Once she was released from her Indentured Servitude duties and had been teaching for a couple years, Deborah became restless. She wanted adventure and to see the world in its entirety. Deborah began sewing herself men’s clothing and contemplating the idea of enlisting. According to the Female Review, she had made the decision to go to Philadelphia but had been delayed due to winter weather. This is when the idea really began to shape itself in the woman’s mind. The possibility the army could offer her were endless and enticing. It was exactly the thrill she had been in search of.

“Before she had accomplished her apparatus, her mind being intent, as the reader must imagine, on the use to which they were soon to be appropriated, an idea no less singular and surprising than true and important, determined her to relinquish her plan of travelling for that of joining the American Army in the character of a voluntary soldier. This proposal concurred with her inclinations on many accounts. Whilst she should have equal opportunities for surveying and contemplating the world. She should be accumulating some lucrative profit; and in the end, perhaps, be instrumental in the cause of liberty, which had for nearly six years enveloped the minds of her countrymen.”

Deborah set off to become a soldier not long after this. The lady naturally had to disguise herself and enlist as a male. This was not a very difficult task. Deborah had a strong muscular build and small breast easily hidden with cloth bindings. The lack of facial hair was not of any concern. The Continental Army regularly enlisted young boys that were not grown enough to for beards. There was nothing unusual that Deborah lacked facial hair. There is some huge debate on whether she enlisted in 1781 or the following year in 1872. Some biographies state it was 1781 while other sources list the date as in 1872. According to an article in the Westchester Historian journal:

“Did Deborah become a soldier in 1781 or 1782? This is the question which has puzzled anyone trying to write about her. In petitioning for back pay and for various pensions, Deborah, in different documents, used both dates. Most people have concluded that the 1782 date is correct; using that date, however, creates many problems that have not been satisfactorily resolved by others. Some things in Mann’s narrative do not check out, although many things in it appear to be true. The people mentioned existed and can be placed where Deborah said, even when at first her statements may not appear logical. Mann’s version of Deborah’s story is the only one that hangs together as a whole. The year of Deborah enlistment may never be conclusively resolved, but there is much in Mann’s manuscript to support the claim for 1781.”

No matter what year the enlistment occurred, Deborah was successful and became a member of the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment of the Continental Army. The most interesting part of this time period was the fact that British General Cornwallis had surrendered in Yorktown on October 19th, 1781. The Revolutionary war was technically won, but the fighting had not ceased. The fight for independence was still going raging all over American soil. The Fourth Massachusetts Regiment was in the thick of these events and now so was Deborah Sampson too. Their goal was to help maintain their win because the British still occupied and controlled many towns.

The Fourth Massachusetts Regiment was compiled of around fifty to sixty men and after Deborah Sampson joined them, the group marched for West Point, New York. The group’s job involved patrolling “no man lands” between the Manhattan area occupied by the British and Worcester. One of the major British units that the regiment faced was led by a well known and feared colonel named James DeLancy.

The group was the most skilled and ruthless of the loyalist Brigades.

The Delancy Brigade was established in September 1776 consisting of three battalions with five-hundred soldiers each. One of the battalions led directly by Colonel Delancy himself found themselves patrolling neutral territory between New York and Worcester around the same time the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment was also doing patrols. This was a common occurrence. Skirmishes and battles did not stop when the British surrendered. Fighting continued for a couple years afterward.

In The National Women’s History Museums article about Sampson by Debra Michals, Ph.D. in 2015, Michals describes Sampson’s time working as a male soldier.

“She was given the dangerous task of scouting neutral territory to assess British buildup of men and materiel in Manhattan, which General George Washington contemplated attacking. In June of 1782, Sampson and two sergeants led about 30 infantrymen on an expedition that ended with a confrontation—often one-on-one—with Tories. She led a raid on a Tory home that resulted in the capture of 15 men. At the siege of Yorktown she dug trenches, helped storm a British redoubt, and endured canon fire …”

Deborah Sampson really held her own during her time short time among the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. It was while on patrol that she saw action and eventually was wounded. She had been cut across the head. Deborah was terrified to receive medical attention because she feared that her gender would be discovered. The soldier was not ready to put away her musket. This lead to Deborah refusing to be taken to the hospital. She tended to her wounds herself and continued on relieved her true identity would remain a secret; unfortunately, it was not long before her regiment was in another skirmish. It was during this fight that the young woman received a musket-ball to her thigh. There was no escaping going to a hospital this time.

Despite refusal to go, her companions carried her directly to the nearest hospital.

In a clever ploy and attempt to avoid her secrets coming out, Deborah distracted the doctor by pointing out her head injuries and insisted that is where her wound was at. She was giving a clean bill of health and released after a very short stay.

The leg injury was rather severe and Deborah did her best to remove the musket-ball from her thigh with a simple pen knife but was unsuccessful. The woman did her best to continue on and act like nothing was wrong. She has been hoping the wound would heal quickly and that all would be fine. Continuing her duties in the Fourth Regiment was difficult and tiring work. Deborah found the work exhausting and terrifying. The Female Review who interviewed the woman soldier themselves claims she was running on pure strength and faith.

“She says she underwent more with fatigue and heat of the day, than by fear of being killed; although her left-hand man was shot dead at the second fire, and her ears and eyes were continually tormented with the expiring agonies and horrid scenes of many others struggling in their blood. She recollects but three on her side who were killed, John Bebby, James Battles and Noble Stern. She escaped with two shots through her coat, and one through her cap…She now says no pen can describe her feelings experienced in the commencement of an engagement, the sole object of which is to open the sluices of human blood. The unfeigned tears of humanity has more than once started into her eyes in the rehearsal of such as scene as I have just described.”

The injuries from being shot with a musket-ball proved to be too severe for Deborah to recover from. She became extremely ill with fever from an infection that had developed from the musket-ball remaining in her thigh. Deborah loses consciousnesses and is admitted to the hospital. It was here that a doctor discovered she was actually a female and not a male as they were told. It was Dr. Barnabas Binney who made the discovery. This definitely spelled out the ending of Deborah Sampson’s military career.

The doctor showed kindness and did not immediately reveal the secret.

The injured Deborah Sampson was allowed to recover and received needed medical care at Dr. Binney’s own personal residence. This would have been an ideal place to become healthy again but complications came up because Dr. Binney’s niece apparently fell in love with Deborah. This forced the issue, and the truth had to come out. The niece was told that the soldier staying in the Binney residence was actually a woman. Deborah went on to report the ruse to the general she served.

John Paterson was a major general of the continental army best known for leading the 1st Massachusetts Regiment and later becoming a member of U. S Congress. General Paterson was from New Britain, Connecticut. He was quite experienced and involved in the political scene surrounding the revolutionary war and the future of the newly freed colonies. When Deborah Sampson confessed the truth and General Paterson was provided a full account of the situation, the man notified General Henry Knox.

It would not take long for these events to reach George Washington himself. The matter was a tricky and difficult one to approach but it was quickly decided to give Deborah Sampson an honorable discharge and all due respect a soldier such as herself deserved for the bravery displayed. This was something to be admired.

General Paterson gave Deborah Sampson encouragement according to the Female Review. Sampson received kind words and offers of safe transportation home.

“He told her, she might not only think herself safe, while under his protection, but that her un-rivalled achievements deserved ample compensation – that he would quickly obtain her discharge, and she should be safely conducted to her friends.”

Documents of discharge were signed on October 25th, 1783 by General Knox. These documents and letters filled with accounts of gallantry and accomplishments while serving the Fourth Massachusetts Regiment. These were presented to Deborah Sampson in person by General William Shepherd, Colonel Henry Jackson, and General John Paterson. According to The Liberty Tree and Valley Compatriot Newsletter, General Paterson’s wife had given Deborah Sampson a dress to wear.

Deborah Sampson went on to marry Benjamin Gannet in the spring of 1785 on April 7th. The couple had three kids named Earl, Patience, and Mary Gannet.

Deborah’s husband Benjamin was a farmer from Sharon, Massachusetts and worked on the lands that had been in his family for generations. The farms’ lands were small and not highly productive; unfortunately, the family faced being close to poverty in the post-war depression many suffered from. The economy just wasn’t doing well because the revolution had many costly.

In Deborah’s later years of life, she often gave speeches and lectures in support of breaking away from traditional gender roles. The presentations usually included her going on stage in uniform to perform elaborate military drills and stories about her services. She shared her experiences in order to improve her finances and justify the actions she took in order to enlist and serve in the Fourth Regiment of Massachusetts.

Deborah and her husband Benjamin raised their children and later adopted a young orphan named Susanna Baker Shepard. Money was still extremely tight which led to her petitioning the state legislature to get money for her military services. The funds had been withheld because Deborah had actually been a woman during her military career.

The money awarded to her and Governor John Hancock signed the order that year. She had been granted thirty-four pounds plus interest back from her discharge in 1783. The money was well earned and deserving

In 1804, Paul Revere wrote to the U.S. Representative William Eustis of Massachusetts on Sampson’s behalf. Revere is best known for his escapades and famous midnight ride in order to alert the colonial militia of incoming British forces right before the battles of Lexington and Concord in 1775. He had taken upon himself to do this task out of respect and support for a noble lady because nobody had ever requested a pension because of the gender issue. Paul Revere wrote:

“Sir, Mrs. Deborah Gannett of Sharon informs me, that she has inclosed to your care a petition to Congress in favour of her. My works for manufacturing of copper, being a Canton, but a short distance from the neighbourhood where she lives; I have been induced to enquire her situation, and character, since she quitted the male habit, and soldiers uniform; for the more decent apparel of her own sex; & since she has been married and become a mother. Humanity, & justice obliges me to say, that every person with whom I have conversed about her, and it is not a few, speak of her as a woman of handsome talents, good morals, a dutiful wife and an affectionate parent. She is now much out of health; She has several children; her husband is a good sort of a man, ‘tho of small force in business; they have a few acres of poor land which they cultivate, but they are really poor. She told me, she had no doubt that her ill health is in consequence of her being exposed when she did a soldiers duty; and that while in the army, she was wounded. We commonly form our idea of the person whom we hear spoken off, whom we have never seen; according as their actions are described, when I heard her spoken off as a soldier, I formed the idea of a tall, masculine female, who had a small share of understanding, without education, & one of the meanest of her sex. When I saw and discoursed with I was agreeably surprised to find a small, effeminate, and conversable woman, whose education entitled her to a better situation in life. I have no doubt your humanity will prompt you to do all in your power to get her some relief; I think her case much more deserving than hundreds to whom Congress have been generous. I am sir with esteem & respect your humble servant, Paul Revere”

It was not long after Revere’s letter had been issued that Deborah was awarded a full military pension. The merits of being a dutiful citizen, mother, and wife was a strong factor that persuaded the voters to go favor Sampson. She began getting paid at a rate of around four dollars a month.

BOOK OF THE DAY:

Masquerade: The Life and Times of Deborah Sampson, Continental Soldier by Alfred F. Young scrapes through layers of fiction and myth to uncover the story of Deborah Sampson, a Massachusetts woman who passed as a man and fought as a soldier for seventeen months toward the end of the American Revolution.

Deborah Sampson was not the only woman to pose as a male and fight in the war, but she was certainly one of the most successful and celebrated. She managed to fight in combat and earn the respect of her officers and peers, and in later years she toured the country lecturing about her experiences and was partially successful in obtaining veterans’ benefits. Her full story, however, was buried underneath exaggeration and myth (some of which she may have created herself), becoming another sort of masquerade. Young takes the reader with him through his painstaking efforts to reveal the real Deborah Sampson in a work of history that is as spellbinding as the best detective fiction.

PLEASE CLICK HERE TO GET A COPY

FOLLOW US ON SOCIAL MEDIA!

FACEBOOK PAGE:TheChroniclesOfHistory

TWITTER: SamanthaJJamesx

INTAGRAM: sammyloveshistory

PINTEREST: thechroniclesofhistoryblog

TUMBLR: samanthajameswriter

JOIN THE HISTORY TABLE GROUP:

Share in a love of history, writing, books, or just reading! Everybody can join who love history. The rules are pretty relaxed. The main ones are to be civil towards each other and keep modern politics out of the discussion.

JOIN OUR GROUP BY CLICKING HERE

BOOKENDS OF LITERATURE GROUP:

Authors and readers alike come share your books, writing, book reviews, and love for all things book! This is a community for writers and readers alike to find a home. Just like the history group, the rules are relaxed. We just ask for civility and kindness towards each other.

JOIN OUR GROUP BY CLICKNG HERE

Hey! Nice work.

Thank you Mark!

I’m not an Americanist, but a friend of mine, who did post-graduate work with Al Young, is; I read Al Young’s book (above) and gather that it is the last word on the subject. Your blog is first-rate!

Your friend worked with Alfred F. Young? The author one of my book recommendations?

Yes, my buddy Walter Wallace–who is the historical preservation coordinator for the town of Rockingham, Vermont, and docent at the Rockingham Meeting House, worked with Al Young at Northern Illinois University and was friendly with the great scholar outside the bounds of the academy.

That is awesome and what a small world. Quite a coincidence Alfred’s book was my book pick of the day. Too funny!

Well, when I saw your subject line with Deborah Sampson’s name, I assumed Al Young’s book was involved.

Hahaha, it is a good book!

Reblogged this on Dave Loves History.

Thank forever and always for the re-blogs! You are the best Dave! 🙂 🙂 🙂

You did the work, I just share it. Keep writing!

I appreciate the support!

Fascinating story, well told! Thanks fr sharing!!

Thanks for the kind comment, and am glad you are liking my post! Appreciate it!

You are very welcome!

A very brave woman well ahead of her time. Willing to fight for what she believed in. Her story needs to be told more to inspire all.

Thank you Terry. She is on of my favorites from American History. I love her!

Gladly elated to read of the Lady Sampson once again as I am fully aware of her many merits. Great piece filled with new data.

I am glad you enjoyed the post!

Keep writing!

Thank you!

What an interesting story you have told! I believe there was also a women who went to serve in the army as a doctor in the Boer War who also had to pretend she was male! Lovely research!

I think there are many cases of this, do you remember the name of the woman from the Boer War? That is really cool!

I have looked it up, her name was James Miranda Steuart Barry, she has a very interesting story, I was mistaken about the Boer War, but not that she served in the military as a ohysician in Cape Town, she also served in other places in the British Empire.

I will look into her, thank you!

Another wonderful and inspiring story – thank you for sharing!

Hey @Chronicles of History; Kudos to you as your work is absorbing 🧽 and tattooes into our consciousness! Great work!🙏♒️🐕👍

I am really glad you are enjoying my articles and appreciate the support so much!

I prize knowledge above all else. I don’t care for stupid. Keep writing

Thanks lol

Pingback: U.S Civil History╽Eyewitness Account of Abraham Lincoln’s Shooting & Death | THE CHRONICLES OF HISTORY